Resurrection of a Painting – Part Two

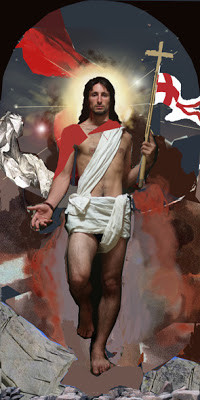

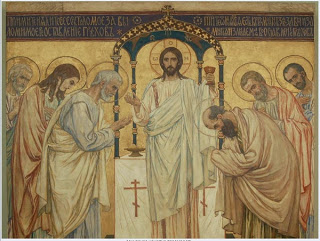

The painting of the Resurrection and accompanying thesis arose as a result of my reflection upon the chapter on “Art and Liturgy” in Cardinal Ratzinger’s book The Spirit of the Liturgy. Specifically, it is first a response to a statement that our Holy Father makes: “All sacred images are, without exception, in a certain sense images of the Resurrection, history read in light of the Resurrection.” Later, after a discussion of the theology of the icon he asks, “Is this theology of the icon, as developed in the East, true? Is it valid for us?

I investigated the development of early Christian art, when the Church was still unified, and studied the connections to theological and cultural developments. I researched the history of the icon in order to understand its context in the Eastern Church. From this arose the idea to combine the Orthodox and the Catholic traditions in one painting of the Resurrection, an image that could be a part of the liturgy in the same way an icon is, but one that uses the traditions and language of beauty developed by the Western masters of the past 1000 years.In my research I read many books and perused several others. Those which I found most interesting and useful were:

1. Alain Besançon, The Forbidden Image: An Intellectual History of Iconoclasm. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2000. I highly recommend this book for anyone iterested in theological and philosophical influences on the development of art.

4. Timothy Verdon, Il Catechismo della Carne. Siena: Cantagalli, 2009. Timothy Verdon’s books are an excellent resource. I do not know of anyone else writing art history from honestly Catholic perspective. Despite being American most of his work is in Italian.

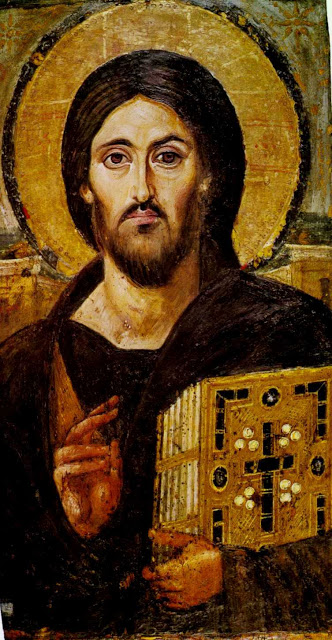

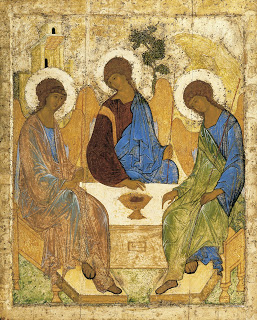

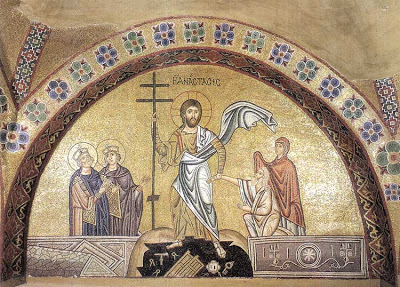

Early Christian faith was anchored in Christ’s Resurrection. The actual episode of Christ’s Resurrection is not narrated in the Gospels, and for this reason we do not see it illustrated until much later in Christian art. Depictions of the Resurrection of Christ came to be represented by the descent of the Saviour into Hades. The theme of the Descent in Hell has it’s origins in the allegorical liberation images of the victorious Roman emperor who drew the defeated peoples toward him and in the god/hero of classical mythology who descends to the lower regions to bring back the dead. Called the Anastasis or Harrowing of Hell it is based on I Peter 3:18-20 and the Apostles’ Creed which states that Christ “descended into Hell” before his Resurrection.

|

| Hosios Loukas Phocis – Greece 11 Century |

|

| Gerdmars 2000 |

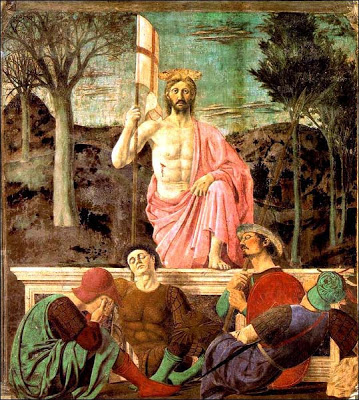

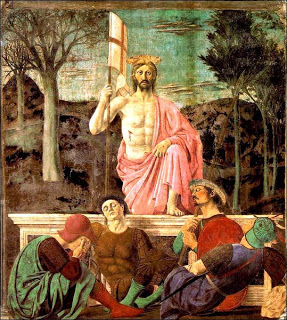

As the west shifted its spirituality to a focus on the cross, the old model of the Resurrection is seen less often. Pictures of the Anastasis degenerate into exercises in artistic imagination as the Resurrection seems to lose its intimate connection with the cross and an understanding of it as an essential part of our salvation. The Harrowing of Hell continued to show up every so often in the work of lesser known painters but in no image that contained the carnal force of the crucifixion or the spiritual power of the best representations in the east. The Resurrection came to be represented by Christ’s exit from the tomb and other Biblical scenes most notably the Supper at Emmaus and Doubting Thomas.

|

| Piero della Francesca 1463 |

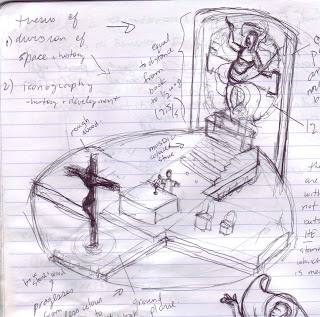

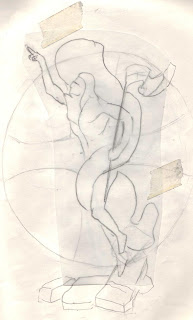

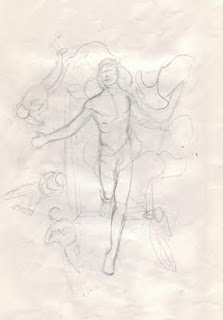

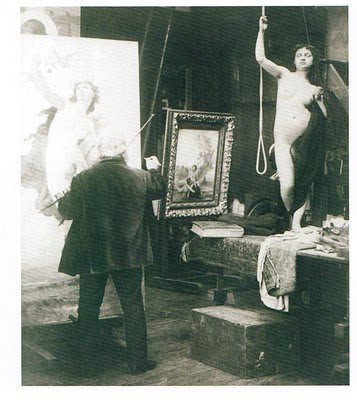

As I drew I searched for an image which would most able to combine the Eastern and Western concepts of the Resurrection. This is what I eventually came up with:

Godfathers of the Renaissance

“Godfathers of the Renaissance” is an excellent PBS documentary on the Medici and Florence of the quatrocentro e cinquecento. You can watch it free on youtube.

Resurrection of a Painting

Below it is presented in situ at San Filipo Neri church in Florence, Italy.

Reflections of Glory

Iconic Developments

The Two Andreis

“Tarkovsky for me is the greatest [director], the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.” – Ingmar Bergman

Sacred Art and Liturgy – Part Two

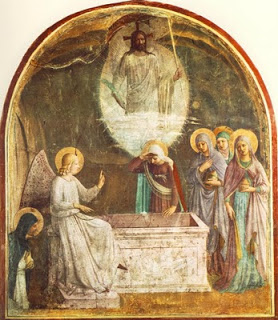

The influence of Franciscan spirituality gave a renewed meaning to earthbound reality and triggered a major transformation in art history. Begining with Giotto, artists began to focus on created reality as a source for artistic inspiration. The artists that followed him in this development continued to paint the Resurrection, which was now imbued with a new significance as artistic developments came to be applied to old models. In the Scrovegni Chapel, Giotto’s inclusion of the sleeping soldiers in his Noli Me Tangere (above) is interesting as it suggests that Jesus has just exited the tomb. This image has its origins in the Rabbula Gospel mentioned in the last post.

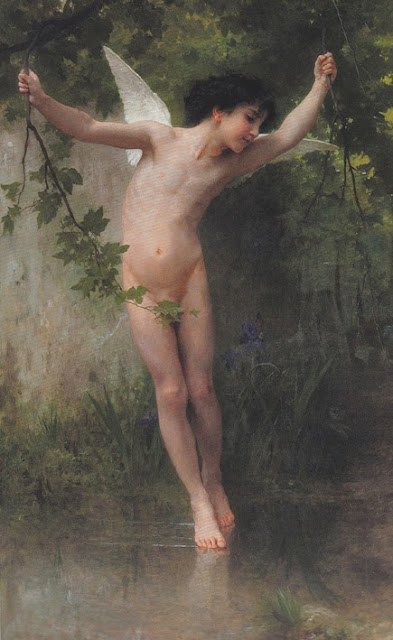

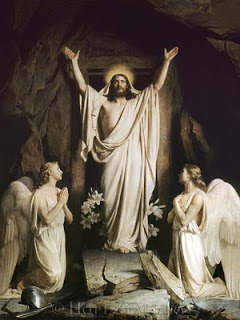

This depiction of the body of Christ, both strong and tender, exiting from his earthly tomb, becomes the model for Western artists’ depiction of the Lord for the next several hundred years.

Tintoretto 1579

Cecco da Carravaggio 1619

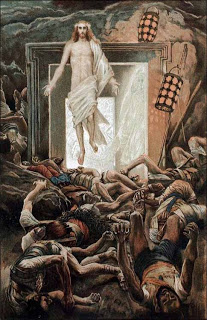

Tissot 1882